At one point, I was coordinating a group of about 20 people playing a geospatial game, using a private group on a Slack instance. We had recently removed a very problematic member from the Slack (he openly admitted to stalking and threatening female players on both teams because he believed they “deserved it”) and he was very upset by being ejected from the community. As I was an admin for the Slack, he also blamed me for executing the community’s decision and terminating his account.

So at this point, the person was not in the Slack instance at all, let alone in the private group.

While I was coordinating everybody, this problematic (former) member opened a message to me through Google Chat. I observed in Slack that he was messaging me, and I immediately received a physical threat in Google Chat to stop talking about him, or he would find and assault me offline. I observed in Slack that he was now threatening me as well, and he immediately responded in Google Chat by increasing his threats.

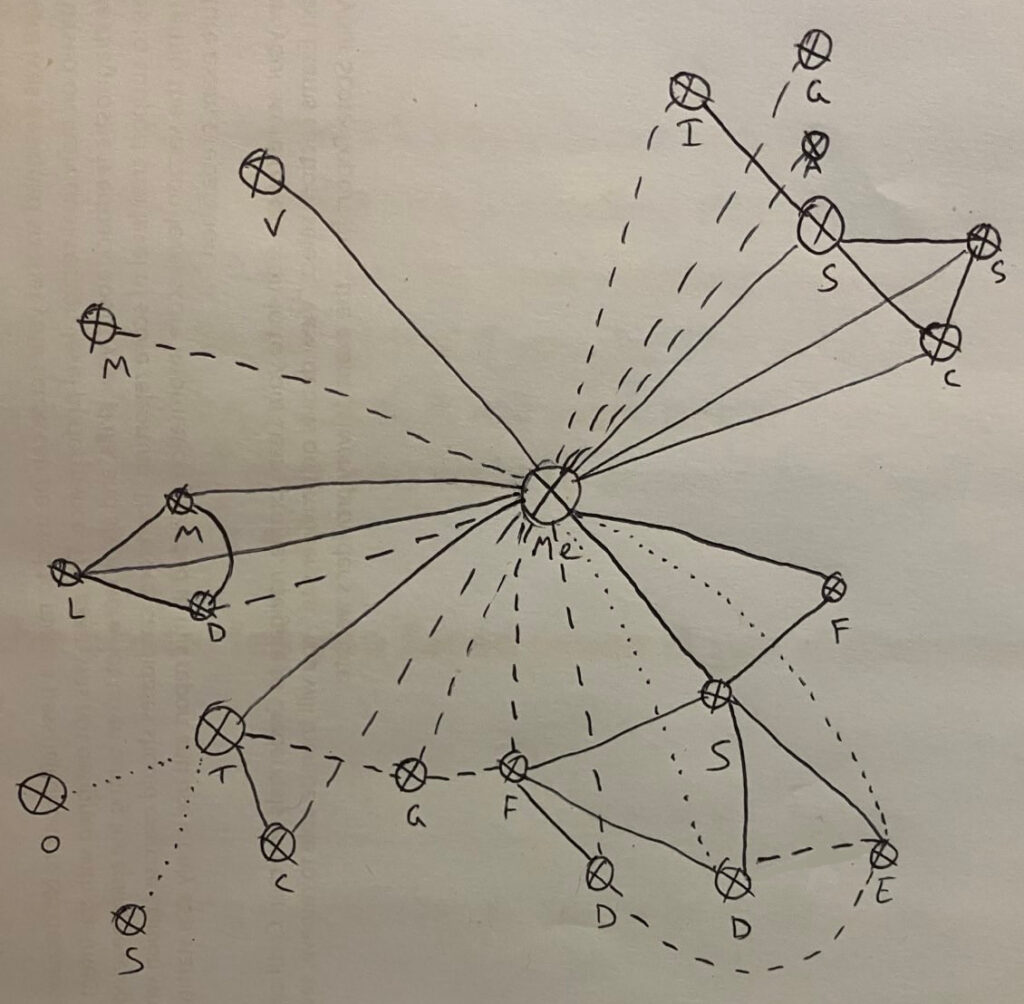

Clearly, there was a breach in security here. It disturbed me on multiple levels. Not only was this person clearly privy to general conversations on the server, but also in this ostensibly private group. We had removed him because of his behaviors, and yet clearly he felt safe and anonymous enough to issue threats to stalk and then physically assault me, while revealing that he had still had access to the community in some fashion or another. It would have been one thing to say maybe a new account had been created that slipped through vetting… but in this private group of roughly 20 people, all were accounted for and known players. That left either service compromise, account compromise, or some player’s active collaboration with somebody who was known to be actively trying to do harm to the community’s members. And receiving threats of physical harm in an attempt to intimidate me was also distasteful, to say the least.

What disturbed me about this? The violation of trust, for one–this was supposed to be a team-only server, and then a private group within that team, with people who were all known and trusted to keep their accounts secured. The service itself was not known to be compromised, and the problem person was not technically accomplished enough to a point where I believed him capable of creating a new compromise. That left active collaboration… but that should have been almost unthinkable.

Further, we had evicted the person from the team because his actions were a threat to player physical safety. He also continually referred to himself in Messianic terms, and that created additional concern for people–there was real possibility that he might decide somebody “deserved” to be assaulted, and he would then follow through on that because he, as the main character, was inevitably correct and justified in everything he did. He literally could do no wrong in his own eyes. While we had contacted law enforcement, we had been told that they could not do anything unless a law was actually broken. That’s understandable, but the community needed to protect itself before somebody was seriously hurt or killed by this aggressor.

However, there were some people in the team who felt that the person was just playing a persona and was cool to hang out with. They were against removing this person from the community, but had acquiesced to majority opinion when the person wouldn’t apologize or moderate his behavior.

I don’t (and never will) know why this person thought he was a Messianic figure, or why he felt this justified stalking, harassing, and threatening physical harm against people who didn’t give him the adulation he thought he deserved. Perhaps the most logical explanation I can construct is that he was mentally disturbed and needed expert attention or medication. Most of the alternate hypotheses I can see essentially boil down to the supposition that he is, simply, an evil person.

In this particular case, we have some information on how this was able to happen. One of the players in the private group was in a relationship with the problematic person, and had left herself logged into Slack. He simply used her access. Now, accounts differ as to whether she had “accidentally” left herself logged in (and he used her access without her active participation), or whether she had deliberately left herself logged in as a way of partially assuaging his fury at having been evicted from the community. Either way, it was not service compromise, nor was it strictly speaking an account compromise… merely a misuse.

There are a host of solutions that could be proposed for this situation. Perhaps the first one that deserves examination is the response of offline authorities: while the RCMP were not in a position to deal with someone who had not yet committed a crime (and I agree that they had no basis on which to intervene, much as we may have wanted them to), the behavior exhibited and admitted was still very problematic. So, perhaps a different sort of intervention, something similar to calling upon child protection services where, if multiple reports were submitted, somebody might be required to go for assessment. Optimally, I would like their online behavior and offline movements to also be tracked, to ensure they do not lash out at people, but this I believe would cross a line–we are still, after all, talking about somebody who has not necessarily taken any unlawful actions. If the goal is to get them help, then actions which feel overly punitive are likely to be counterproductive.

On the technical side of things, there are ways that services can allow users to expire all their user sessions at once. Admins can also trigger this for specific users, sometimes. But here lies a problem with that course of action: we did not know, at the time the threats were being made, whose access was being used to allow the problem person to snoop on a community from which he had been evicted. It might be handy to have a method to “instant re-lock” a private group, immediately suspending everybody’s access and forcing them to reauthenticate on the spot… but that will not prevent other players from intentionally reauthenticating and then allowing the problem person to maintain access under their credentials. It’s also an incredibly blunt tool–you would essentially penalize 19 “good” players by forcing reauthentication on all their devices, for the sake of rooting out the 1 “bad” player whose access was being misused (when they might just bypass it again anyway). And as group sizes go up, the number of people inconvenienced for the sake of attempting to block out the one problem account would increase as well.

It’s also important to consider possible DoS attacks, for both of these proposed “solutions”. That is, if sufficient people submit reports, could somebody be unwillingly pushed to go for assessment? Yes, clearly! Similarly, assume some scallywag decides to keep hitting the “instant re-lock” button for funsies. That would also cause no end of troubles for everybody in the group, and could functionally lock them out of the community for longer periods of time. (I find that the flip-side of security is often outright denial of service, whether that is voluntarily, involuntarily, or self inflicted.)